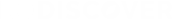

2020 marks the centenary of the birth of Paul Celan—seen by many as the greatest poet of the post-war period—and 50 years since his death by drowning in the river Seine. To honour his work and legacy, we’re bringing to your attention painter Anselm Kiefer and ceramicist and writer Edmund de Waal, whose works have been inspired by Paul Celan’s poetry.

Who was Paul Celan

Paul Celan (1920-1970), was born as Paul Antschel (Celan is an anagram of the Romanian spelling of “Ancel”) in Cernăuți / Czernowitz, today Chernivtsi, in western Ukraine, the capital of Bukovina, a province of the Habsburg Empire that at the time belonged to Romania. He came from a German-speaking Jewish family and while his father gave young Paul a Jewish education, his mother exposed him to the works of German poets Rilke and Schiller and instilled in him her love for the German language and culture.

In 1938 Celan moved to France to study medicine, but returned to Romania before the outbreak of World War II in order to study literature and Romance languages. Unfortunately, 1942 both his parents were deported to concentration camps in Transnistria and later died, while Celan was sent to a labor camp for a year and a half. After being liberated at the end of the war, Celan moved to Bucharest and later Vienna, before finally settling in Paris, where he remained for the rest of his life. In Paris he supported himself as a translator and senior lecturer in literary history and German at the École Normale Supérieure until his suicide in 1970.

Paul Celan and a new poetic language

Although Celan was fluent in many languages, lived in a French environment and was influenced by French surrealism, he wrote his groundbreaking poems in his mother-tongue German. This was often a constant source of tension for him, since it was the language of his parents’ criminals. In order to be able to write poems in German, Celan felt that he needed to find his own language and his own way of expressing himself. Creating his own poetic language was supposed to help him deal with the Holocaust and all the crimes committed during the war. At the same time, he was also trying to keep all the horrors in mind while aiming to build a better future. He pushed the boundaries of language and his poems reflect a conflict between the language of poetry, the language of criminals and the language of everyday life.

A language artist, Celan is famous for inventing his very own words, which are not found in everyday language. His brilliant neologisms —”breathturn”, “wordwall”, “slowsound”, “smokethin”—conceived by crashing words together, and surreal imagery are a testament to his beautiful and enthralling imagination, and also make him famously difficult to translate.

Anselm Kiefer’s paintings inspired by Paul Celan’s poem “Death Fugue”

Born in 1945, Anselm Kiefer is a German painter and sculptor, known for his large scale work and use of a variety of materials and media, most often straw, ash, clay, shellac and lead. The past plays an important part in Kiefer’s work—Donaueschinge, the town where he was born, in the family’s cellar and improvised bomb shelter, was s a military garrison during WWII, and the ruins of the war served as his playground. Moreover, he was also one of the first German artists to address the Nazi crimes, in a series of photographs and performances called Occupations and Heroic Symbols.

Kiefer often credited the poetry of Paul Celan to have had a key role in developing his interest in Germany’s past and the cruelty of the Holocaust, and frequently dedicated paintings to him. Most importantly, two of his most renowned paintings, Your Golden Hair, Margarete and Sulamith, are drawn directly from Celan’s most famous poem, Death Fugue (Todesfuge), that depicts a disquieting image of a concentration camp.

While many critics often argue that the poem’s beautiful lyricism and aesthetic don’t do justice to the horrors of the Holocaust, others consider it a masterful description of fear and death. In referrence to it, acclaimed American critic John Felstiner said it was “the ‘Guernica’ of postwar European literature”.

Black milk of dawn we drink you at night

we drink you at noon death is a master from Deutschland

we drink you evenings and mornings we drink and drink

death is a master from Deutschland his eye is blue

he strikes you with lead bullets his aim is true

a man lives in the house your golden hair Margarete

he sets his dogs on us he gifts us a grave in the air

he plays with the snakes and dreams death is a master from Deutschland

your golden hair Margarete

your ashen hair Shulamit

The final lines of Death Fugue by Paul Celan, taken from Memory Rose into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry, translated by Pierre Joris (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020)

In the two paintings, Kiefer’s focal points are two figures who are contrasted in the poem and act as its central metaphor. On one hand there’s Margarete, with her cascade of blonde Aryan hair, and, on the other, Sulamith, a Jewish woman whose black hair indicate her Semitic origins, but which is also ashen from burning.

To suggest Margarete, the Germans with their long, blond hair, Kiefer paints, glues and scratches blades of straw like rays of light tipped with a pinkish flame. For Sulamith—a direct reference to the heroine of the Song of Solomon—the artist used oil, emulsion, woodcut, shellac, acrylic, and straw, resulting in a thick impasto. Kiefer’s painting depicts a real Nazi Memorial Hall in Berlin, but his hall has nothing patriotic in it, it is a gateway to damnation, and a road to hell. In his bold Sulamith, he transformed architecture meant to honour Nazis into a memorial for their victims.

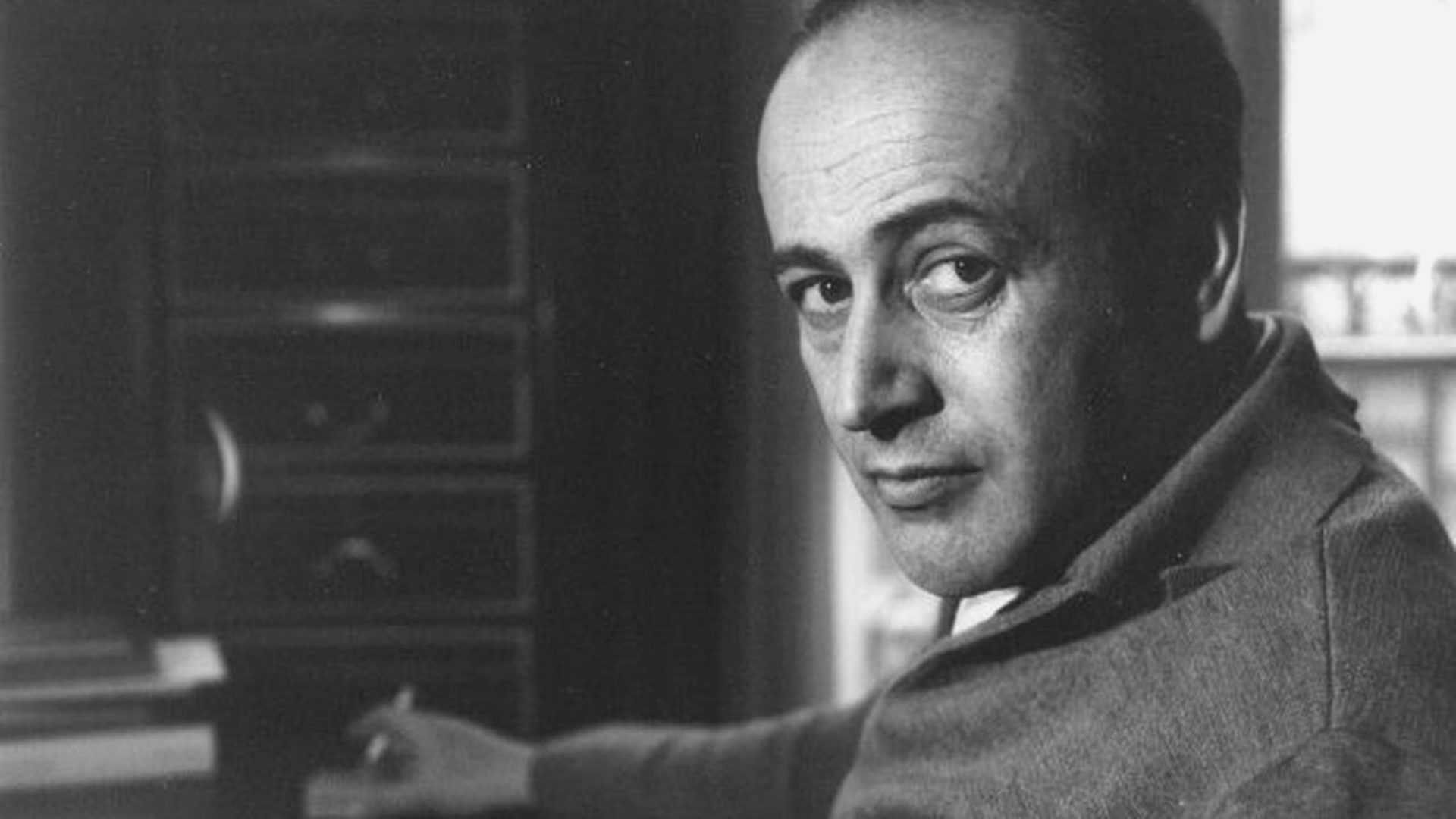

Edmund de Waal’s artwork influenced by Celan’s poetry

Born in 1964, Edmund de Waal is, in his own words, an artist who writes. He is mostly known for his large-scale porcelain installations and in his work he investigates themes of diaspora, memory, materiality and the colour white. His interventions and artworks are made for various spaces and museums around the world.

In 2013, in New York, de Waal exhibited 22 installations, one oh his largest exhibitions until that point, in a series called Atemwende (breathturn). It was named after Paul Celan’s 1967 poetry collection of the same title, a term that, according to the poet, expresses the moment when words transcend literal meaning. The exhibition was constructed as a conversation with the poetry of Celan and emphasised de Waal’s understanding about music and architecture.

In 2016, de Waal debuted a Celan-inspired piece for the Gagosian Gallery in London. in Czernowitz (for Paul Celan), and the other accompanying works in the series, are extremely personal, a series of elegies for people and for places—his great-grandfather, the poet Paul Celan, and the cities of Odessa, Czernowitz and Paris. The tribute work consists of 10 porcelain vessels, 4 silver pieces, 5 tin boxes and lead elements in 3 black aluminium and plexiglass vitrines.

The artist had been interested in Celan’s work for a long time. He had been known for having the poet’s work scattered around his studio, and using the white space in his works in the same way the poet uses the white page, stating that

“Celan has been really important to me. He’s always dealing with memory. Celan is a poet of loss and fragmentation—he breaks up language and puts it back together again.”

Edmund de Waal

Most recently, in 2019, Edmund de Waal presented breath, an homage to the Romanian-born poet, for Ivorypress in Madrid. The project consisted of a book that the artist had been working on for years. Taking its inspiration from the work of Paul Celan, especially his relation with the weight of words and the colour white, the artwork—made from paper, porcelain, gold, and fragments of manuscript—explores the materiality of books and the traditional processes of binding, paper-making and printing, turning the book into a wonderful and poetic work of art.